This article gathers a few fancy considerations on the various clefs for use with bowed instruments.

Cello scores usually define pitches using either a bass clef or a tenor clef. Advanced cellists who venture into high pitches even use the treble clef.

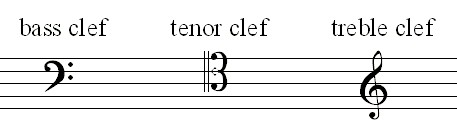

Musicians know that the bass clef is an F-clef, the tenor clef is a C-clef and the treble clef is a G-clef. This figure shows the three cellist clefs:

(Learners who want to know more about clefs can click that hyperlink and display, in a new tab, the corresponding web page of Wikipedia.)

The F, C and G reference notes designated, respectively, by the bass, tenor and treble clefs form two fifths. Like violins and violas, cellos are tuned in fifths. The coincidence is worth noticing.

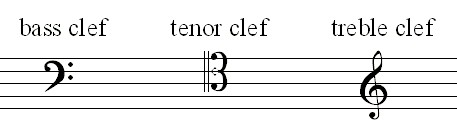

This figure shows the four cello string pitches represented by the three cellist clefs:

Attentively examining the vertical position of the bass clef and that of the tenor clef on the staff shows that they coincide. The double coincidence is twice worth noticing.

Here is the cellist cleverness. Provided they memorize the key signature (that is, sharps or flats that characterize the tonality) of the piece, when cellists need to switch from the tenor clef to the bass clef, they just have to switch from one cello string to the next — and vice versa.

Moreover, although they seldom use the treble clef, cellists who ever need to switch from the treble clef to the tenor clef just have to jump to the second next string — and vice versa.

The twofold coincidence of fifths facilitates reading cello scores across clef changes. Joyful cellists!

Violinists only use the treble clef. They don't have to switch between clefs. Joyful violinists, too!

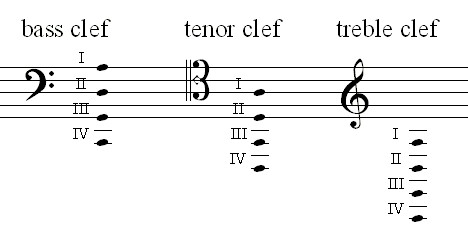

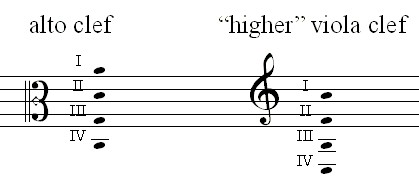

As for violists, they somehow suffer from using either the treble clef or the alto clef, a C-clef that does not facilitate reading across clef changes. This figure shows the four viola string pitches represented by the two violist clefs:

Because the alto clef and the treble clef are vertically unaligned on the staff, switching from one clef to the other requires a reading effort that may discourage beginners.

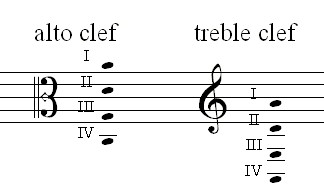

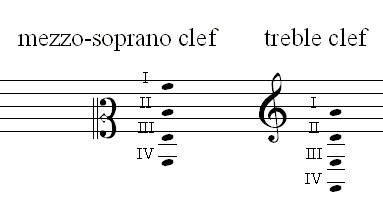

Instead of their traditional alto clef, violists had better use the mezzo-soprano clef, vertically aligned with the treble clef. This figure shows the four viola string pitches represented by the mezzo-soprano clef and the treble clef:

Using the mezzo-soprano clef would facilitate reading across clef changes, just by switching from one viola string to the other, as cellists do.

An alternative for easy switching could consist of moving the G-clef one staff line above, thus defining a new viola clef. Let me name that one “higher” viola clef. This figure shows the four viola string pitches represented by the traditional alto clef and that fancy “higher” viola clef:

To sum up, because the traditional alto and treble clefs are vertically unaligned, reading scores across clef changes requires some reading effort from violists.

The effort, however, must not be considered insuperable. Just think of organists who have to read three staves with treble clefs, bass clefs and C-clefs that can stand on any staff line — not mentioning clef changes! And think of conductors who have to read a number of such different staves where a number of transposing instruments play pitches different from the written pitches!

As a conclusion, violists can suffer from switching between clefs that are unaligned. Violinists don't bother with different clefs. Cellists more easily switch between both clefs they most use.

Clever cellists!

Etymologists disagree on the origin of clever. Let me assert it originates from clef.

Who knows? ●

|

Jean-Pierre Vial March 2020 |

|