This article questions the rigorousness in musical notation and score writing. It refers to certain notions of acoustics.

When you start reading a score, below the piece title and composer's name, you usually come across a tempo marking (for instance, adagio, moderato, allegro, etc.) and often an Italian phrase (for instance, affettuoso, scherzando, maestoso, etc.) that tells you how you should perform the piece.

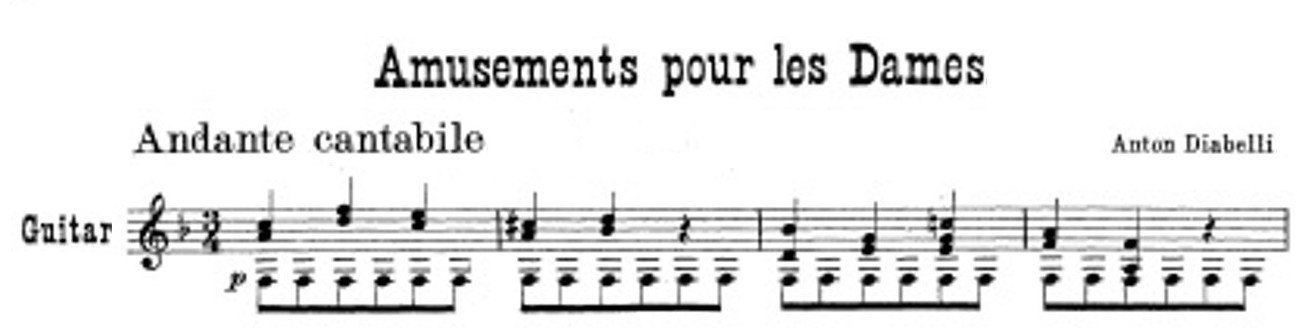

Here is an example of a score header:

Both markings are merely hazy instructions. Even when a tempo marking comes with a metronimical specification (for instance, M.M. O = 40) very few soloists or conductors will refer to the metronome pulse and stick to the desired tempo. Much of these tempo and expression instructions is left at the performer's discretion.

Further on, the score proper is more or less a graph where you read the time from left to right (on the “abscissa”) and, in every stave, you read the note pitches from bottom to top (on the “ordinate”). Because all instruments do not play simultaneously, and wind instrumentalists have to breathe, a few rests complete the score.

When you play an instrument, time unfolds more or less quickly depending on the tempo, and the note pitches correspond to frequencies of emission of sounds. It is therefore commonly assumed that a score consists of series of notes, or else “frequencies” that the composer skillfully positioned in time.

Considering, however, that time (measured in seconds) and frequencies (measured in Hertz — Hz) depend upon one and the same physical unit —time,— somewhat paradoxically, when you play an instrument it is not the frequency which depends upon time, it is the air pressure.

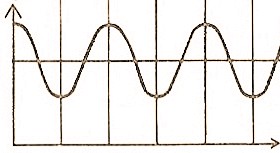

This figure shows how the air pressure varies when a “pure” (purely theoretical, indeed) sound is emitted:

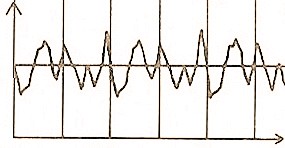

Actually, all instruments produce harmonics which alter that theoretical waveform according to the timbre of the instrument. Here is an example:

To throw light upon the above paradox, let's say you are driving a car on a 50-mph limited road and entering a 30-mph limited area. Depending on whether you are a nervous or placid driver, you adjust your speed more or less quickly. (Silly or novice drivers can even stop at the speed limit and then drive off again at 30 mph.) In any case, it is not the car speed which depends upon time, it is its position. Paradoxically, one cannot simultaneously and precisely determine the speed and the position of an object. (This does not prevent you, however, from being flashed for speed at a particular location: police do not bother with such physical considerations.)

Back to music notation, changes in note pitches (as a shortcut, some people would say “frequencies”) come with a number of extraneous transient frequencies: this is the attack of a note. Depending on whether you are playing staccato, tenuto, or legato, the air pressure and the extraneous frequencies vary quite differently. (Not mentioning portamento, tremolos, trills and other various ornaments.)

Sudden changes in dynamics (for instance, pf, fp, sfz, etc.) also come with a number of extraneous frequencies. Likewise, sudden changes in rhythm (for instance, ritenuto, rubato, etc.) can alter the perception of sound.

Someone will object that pitch, dynamics, or rhythm changes generate extraneous frequencies that can't be perceived. This is partly true as long as you play legato, with sounds in the medium (a few hundred or thousands of Hz) and you play notes whose duration (a few fractions of a second) does not require an exceptional virtuosity.

This is no longer true, however, when playing in the bass (a few tens of Hz) and in a fast tempo. If you play a series of sixteenth notes in the low end of a double bass or a tuba, the effect is “pasty”. Try and play this series at one stretch on a double bass (or click to hear it):

The audience, if any, has difficulty understanding. Then compare with the same series four octaves higher on the violin (click to hear it):

By the way, that is the reason why, in the orchestra, the bass parts are usually less loaded than higher parts. If instrumentalists (especially, bassists and cellists) did not demand some animation in their playing, composers would gladly populate their scores with “pigeon eggs” (meaning whole notes).

Given the above discussion, reducing a score to a series of frequencies which depend upon time sounds like a hoax. A score is rather a canvas from which instrumentalists can widely deviate in terms of tempo, expression, and also of articulation and music rendering at large. (Not mentioning ossia alternatives, cadences and other phrases that composers themselves specify ad libitum.)

As a conclusion, the musical rendering of a piece is a shared responsibility of the composer and the performer(s). The score proper is just a musical construct. ●

|

Jean-Pierre Vial August 2020 |

|