This article analyzes rhythms and their relationships with the natural accentuation of certain notes according to note positions on strong or weak beats.

A musical score is punctuated by a succession of bars (meaning measures, not pubs!) chosen so that every measure begins on a downbeat.

There are two main types of rhythms, binary and ternary. More complex rhythms can then be analyzed as combinations of binary and ternary rhythms.

In a 2-beat measure (for instance, a march), the first beat is strong and the second is weak. By assigning a relative strength index to every beat, we can represent the (duple time) measure in the form [1, 0].

Most often, a beat is itself subdivided into 2 (sub)beats. Each subdivision follows the same rule [1, 0]: the first (sub)beat is strong and the second is weak. It does not matter whether the measure is noted using 2 beats or 4 beats. Many dances are 4 (2 x 2) beats, indeed.

We can reiterate such a binary subdivision and apply the same rule [1, 0] to each subdivision. The next iteration would produce an 8 (2 x 2 x 2) beat measure.

In order to assign a relative strength index to every beat, we have to juxtapose the relative strength indexes, from right to left, in the order of the successive subdivisions. Because, in every subdivision, the relative strength index is binary [1, 0], the relative strength index thus determined is expressed in the binary system.

This table shows the result for a 4-beat dance (for instance, a fox-trot) :

| 1st beat | 2nd beat | 3rd beat | 4th beat | |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in binary system) | 11 | 01 | 10 | 00 |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in decimal system) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

This table shows the result for an 8-beat dance (for instance, a cha-cha-cha) :

| 1st beat | 2nd beat | 3rd beat | 4th beat | 5th beat | 6th beat | 7th beat | 8th beat | |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in binary system) | 111 | 011 | 101 | 001 | 110 | 010 | 100 | 000 |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in decimal system) | 7 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

This noteworthy mathematical property results from the above rules:

To determine the relative strength index of any beat in a binary rhythm, we only have to revert the binary representation of the distance (counted in number of beats) from that beat through the end of the measure.

This table shows that mathematical property for an 8-beat measure:

| 1st beat | 2nd beat | 3rd beat | 4th beat | 5th beat | 6th beat | 7th beat | 8th beat | |

| Distance from the beat through the measure end (in binary system) | 111 | 110 | 101 | 100 | 011 | 010 | 001 | 000 |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in binary system) | 111 | 011 | 101 | 001 | 110 | 010 | 100 | 000 |

In a 3-beat measure (triple time), the first beat is strong and the weakest beat can be the second (most often) or the third (less often).

In a passacaglia, the 3 successive beats are weaker and weaker. Now expressing their relative strength indexes in the ternary system, the 3 beats can be expressed as [2, 1, 0]. (The relative strength index still expresses the distance from the beat through the measure the end.)

In a minuet or a waltz, the weakest beat is the second one. The 3 beats can then be expressed as [2, 0, 1]. (Here, the relative strength index no longer expresses the distance from the beat through the measure end, it is just an index specific to a beat.)

The 3-beat measure is most often subject to a binary subdivision. It is seldom subject to a ternary subdivision.

When encountering a 9 (3 x 3) beat measure, however, we can apply the same reasoning as above, considering the relative strength indexes of every subdivision, and forming the relative strength index for every beat by juxtaposing the relative strength indexes, from right to left, in the order of the successive subdivisions.

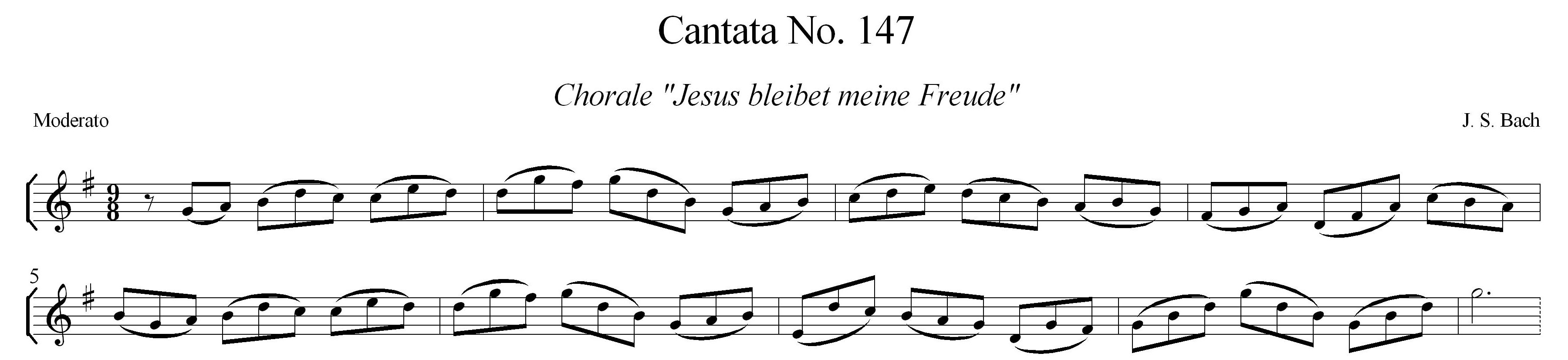

Here is the theme of the chorale “ Jesus bleibet meine Freude ” from J.-S. Bach's cantata n° 147 (click to listen):

In that example, the 9 (3 x 3) beat measure is analyzed as two ternary subdivisions of the minuet type [2, 0, 1]. This table shows the result for the 9-beat measure:

| 1st beat | 2nd beat | 3rd beat | 4th beat | 5th beat | 6th beat | 7th beat | 8th beat | 9th beat | |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in ternary system) | 22 | 02 | 12 | 20 | 00 | 10 | 21 | 01 | 11 |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in decimal system) | 8 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 4 |

The same reasoning applies to heterogenous subdivisions (binary and ternary).

In a 2-beat measure subdivided into 3 (sub)beats (for instance, a siciliana), we would form the relative strength index of every beat by juxtaposing relative strength indexes, from right to left, in the order of successive subdivisions. Most often, the 3-beat subdivision is of the minuet type [2, 0, 1].

Mixing binary and ternary subdivisions creates an apparent difficulty, which is how to choose the right (binary or ternary) numbering system but, because the desired result is just a relative strength index (and no absolute value), the ternary system easily outweighs the binary system.

This table shows the result for the 6 (2 x 3) beat measure:

| 1st beat | 2nd beat | 3rd beat | 4th beat | 5th beat | 6th beat | |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in ternary system) | 21 | 01 | 11 | 20 | 00 | 10 |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in decimal system) | 7 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 |

The same reasoning applies to 3-beat measures subdivided into 2 (sub)beats (for instance, a waltz). This table shows the result for the 6 (3 x 2) beat measure:

| 1st beat | 2nd beat | 3rd beat | 4th beat | 5th beat | 6th beat | |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in ternary system) | 12 | 02 | 10 | 00 | 11 | 01 |

| Relative strength index of the beat (in decimal system) | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

Note: it is customary to note a (triple time) waltz using 3-beat measures. A number of Viennese waltzes, however, in which the measures go in pairs, would perfectly adapt to 6 (2 x 3) beat measures, or even 12 (2 x 3 x 2) beat measures for which we would apply the same reasoning.

The music of Eastern Europe often uses more complex rhythms, for instance 5- or 7-beat measures.

Actually, these are combinations of binary and ternary rhythms. For example, we can analyze a 5-beat measure as a combination of either 2 + 3 beats or 3 + 2 beats. Likewise, a 7-beat measure is often a combination of 4 + 3 beats.

In any of these combinations, the main subdivision of the measure includes an element of each type (binary and ternary). In order to determine the strong or weak beats of the measure, we just have to apply the previous reasoning, keeping in mind that the first (binary or ternary) element encountered begins with a downbeat.

Actually, these complex measures (for instance, 2 + 3, 3 + 2, 4 + 3) are often noted using dotted bar lines, making analysis easier by returning us to the previous discussion.

Syncopations are occasional anomalies of accentuation of certain notes of the melody. Most often, only the melody is syncopated, and its accompaniment remains subject to the normal rhythm of the piece. By the way, it is the reason why we can notice the syncopation.

A composer who would like to syncopate both the melody and its accompaniment, more logically, had better occasionally modify the rhythm and the bar positioning.

On upbeats, the composer often places passing notes, extraneous to the key, that help enrich the harmony of the piece.

As an example, let us go back to the theme of the chorale of J.-S. Bach's cantata n° 147, by arbitrarily modifying the weaker beats in every measure (with slightly altering the accompaniment so it can support the melody thus modified). In this (rather rough!) example, the 5th and the 8th beat of every measure have been altered (lowered or raised) by a semitone (click to listen):

The theme takes on a different color, without being completely distorted.

As a conclusion, on upbeats, (almost) everything is allowed.

Sorry, Johann-Sebastian! ●

|

Jean-Pierre Vial November 2020 |

|