|

|

|

In the minor key, degrees VI and VII are varying. In the score, we represent the minor key on a staff whose key signature is borrowed from the relative major key. Representing degrees VI et VII, when raised by a semitone, therefore requires certain alterations (sharps or naturals).

Here is the theme of J.-Ph. Rameau's Le tambourin:

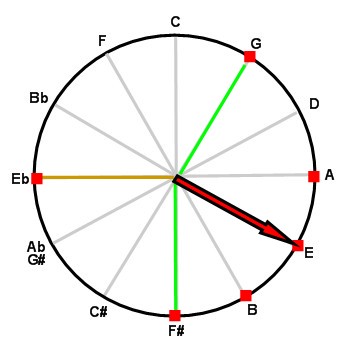

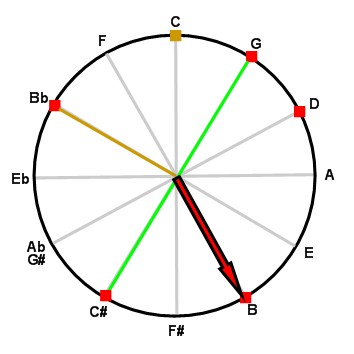

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

The first two bars, further repeated in the theme, contain all notes characteristic of a minor key and mode. On the circle of fifths, the notes are widely spread, but remain compatible with the minor key and mode.

On the score, we represent the theme using the key of E minor, on a staff whose key signature includes a single sharp, as though we were using the relative key of G major. Representing the leading (sensible) note (D sharp) requires a sharp which is not part of the key signature. As we would do in the major scale, we write the leading note D sharp, rather than E flat, so as to distinguish the two degrees formed by the leading note and the tonic.

On the circle of fifths, the arc delimited by the green radiuses is part of the semicircle that represent the relative major key. The brown radius leads to degree VII, the leading note, extraneous to the relative key of G major. (In the tone of G major, that note would suggest a modulation towards E minor.)

That first example is simple for these reasons:

Here is the theme of J.-S. Bach's Toccata in D minor:

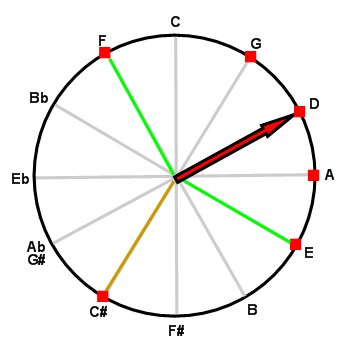

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

Except for a rotation, the representation on the circle of fifths is similar to J.-Ph. Rameau's. The theme contains all notes characteristic notes of the key of D minor.

On the score, we represent the theme on a staff whose key signature includes a single flat, as if we were using the relative key of F major. Representing the leading note (written C sharp, rather than D flat) requires a sharp which is not part of the key signature.

That example highlights a new effect of our auditory memory. With or without acoustic reverberation, rests that follow a note (A and D, in the example) prolong that note in our memory. In the theme, rests emphasize the tonal importance of the notes they follow. Those notes (A and D, in the example), which form an interval of fifth (that is, a perfect cadence), are enough to state the key of D.

Moreover, the first three notes stress the A, making it heard repeatedly and for some time. That note group, an ornament named mordent, emphasizes the tonal importance of the note thus ornamented (the dominant, in the example).

As is the case in J.-Ph. Rameau's theme above, J.-S. Bach's theme includes no note extraneous to the key. Considering that a minor scale can use up to nine notes of the chromatic scale, it leaves little room for extraneous notes, indeed. Only degrees I, III and IV raised by a semitone can be considered extraneous notes.

In a minor key, as is the case in a major key, an extraneous note can disqualify (by making the tonal compass rotate towards) the subdominant or yet further, or it can disqualify the leading note by making the tonal compass rotate towards the dominant or yet further.

The examples below show how composers use those degrees raised by a semitone:

Here is the beginning of F. Schubert's Serenata “Leise flehen meine Lieder” excerpted from Schwanengesang (Swan song):

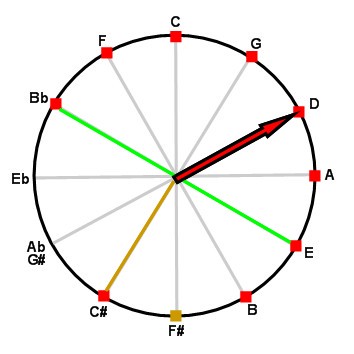

Here is the representation of the corresponding notes on the circle of fifths:

After a short introduction (not shown), the first four bars contain all notes characteristic of the key of D minor. Moreover, in the beginning, the perfect cadence (A → D), where the sequence A → B b → A (of the inverted mordent type) emphasizes A, strengthens the perception of the key of D minor.

On the score, we represent the theme on a staff whose key signature includes a single flat, as if we were using the relative key of F major. On the circle of fifths, the green diameter delimits the semicircle that represents the relative major key. The brown radius leads to the leading note.

Despite a short modulation (in bars 13–16) towards the relative major key, the key of D minor prevails up to bar 24, where degree III, raised by a semitone (F sharp, the brown note), comes as if it were part of the tonic chord. In that false tonic chord (succession D → A → F #→ D), the extraneous note sets forth a modulation towards the major mode of the current key (or towards the subdominant).

Both keys with opposite modes (D minor and D major, in the example) are sometimes called homonym keys.

Here is the theme of F. Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody n° 13:

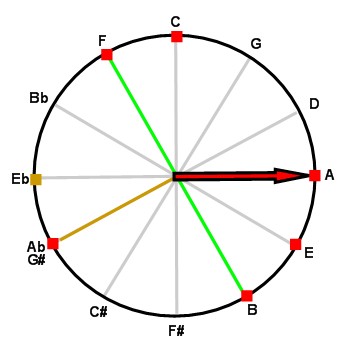

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

The initial repeat of E, on which the next two bars still insist, indicates the tonal importance of the note (dominant, in the example), whereas the arpeggios at bars 4 and 5 state the key of A minor.

On the score, we represent the theme on a staff with no key signature, as if we were using the relative key of C major. On the circle of fifths, the green diameter delimits the semicircle that represents the relative major key. The brown radius leads to the leading note (written G sharp, rather than A flat).

D sharp (or E flat, the brown note) is extraneous to the key of A minor. Yet the theme repeats it with insisting, whereas the normal subdominant (D) is absent. In his theme, Liszt uses the Hungarian (gypsy) minor mode, in which degree IV (subdominant) is raised by a semitone.

On the score, representing the Hungarian minor requires an alteration (sharp or natural) of both degrees IV (subdominant) and VII (leading note).

Here is the theme of M. Ravel's Tzigane:

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

The initial repeat of B, again repeated at the second bar, indicates the tonal importance of the note (tonic, in the example). Moreover, at the first bar, the sequence B → A # → B (almost a mordent type ornament, in which A sharp, a semitone below B, plays the role of a leading note) emphasizes B. The subsequent D forms an interval of minor third that states the key of B minor, although no dominant is present.

On the score, we represent the theme using the key of B minor, on a staff whose key signature includes two sharps, as if we were using the relative key of D major. Representing the leading note (A sharp) requires a sharp which is not part of the key signature.

On the circle of fifths, the green diameter delimits the semicircle that represents the relative major key. The brown radius leads to the leading note (written A sharp, rather than B flat).

C natural is an extraneous (brown) note repeated several times. It is constitutive of the Neapolitan cadence, commonly used in the tzigane style.

|

Jean-Pierre Vial January 2021 |

|

|

|

|