|

|

|

Let us start with simple examples of a major key. As explained earlier, major keys are simpler because degrees VI and VII are unvarying there.

Here is the theme of the chorale “Jesus bleibet meine Freude” (Jesus, may my joy remain) from J.-S. Bach's cantata n° 147:

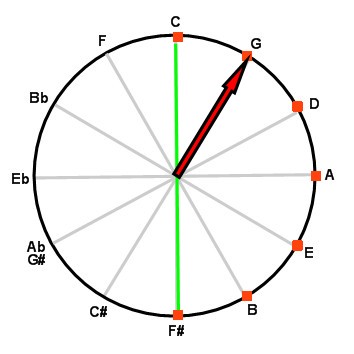

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

The circle of fifths is divided into two semicircles, with the seven notes of the major scale occupying exactly one of the two semicircles.

The first bar of the score contains all notes characteristic of a major key and mode. The first musical impression is the right one. Because our auditory memory has immediately recorded the key, the subsequent notes state that key in a somewhat redundant manner.

On the score, we represent the theme using the key of G major, on a staff whose key signature includes a single sharp, so as to save writing. (Only disturbed minds would represent that theme in a key of F x major or A bb major.)

The above example is quite simple for these reasons:

The subsequent examples will show some difficulties encountered when one or more of the previous conditions is no longer satisfied.

Beyond the theme of the chorale, the first note extraneous to the key of G major is a C sharp, as though the needle of our tonal compass were rotating towards the next key clockwise.

When, as here, the needle rotates clockwise, it disqualifies the leading note (degree VII, furthest from the tonic) with taking its place. In its rotating movement, the needle of our tonal compass also drives the tonic. That is why C sharp gives notice of a modulation towards the closely related key of D major (or maybe B minor).

Conversely, when a note extraneous to the key makes the needle rotate counterclockwise, it disqualifies the subdominant (degree IV, close to the tonic) with taking its place. In that reverse movement, the needle of our tonal compass also drives the tonic. After modulating towards D major, encountering a C natural brings the tonic back to G major (or maybe E minor).

On the circle of fifths, a closely related key corresponds to a slight rotation of the needle of our tonal compass. On the score, it corresponds to a slight modification (at the option of the composer) of the number of sharps or flats in the key signature of the staff.

Composers use modulations for developing a theme and breaking up the monotony of their piece, but they must first state the theme. In order for a theme to be easily recognized, composers refrain from including modulations in the theme or, if they do so, they only include transient modulations that quickly bring back to the initial key.

Often, in classical music, the theme is repeated, or begins with a phrase repeated further in the theme. This other presentation of Bach's theme highlights the repeat:

The theme is therefore the initial phrase, subject to repeat with or without modification. In simpler cases, such as a canon, the theme is repeated without modification. In a fugue, it can be taken from the dominant, the subdominant, or any other degree. It can also be repeated in the relative key. In all cases, by insisting on the initial phrase, the repeat states the theme.

Here is the theme of the adagio from L. v. Beethoven's sonata n° 8 (“Pathetic”):

Beyond the theme, that single phrase is repeated an octave above.

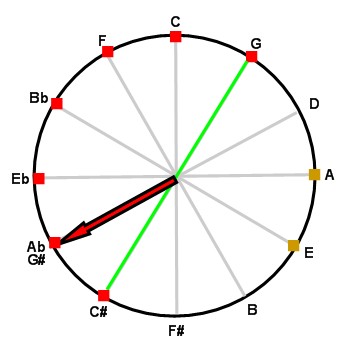

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

The first three bars of the score contain all notes characteristic of a major key and mode. The key is unambiguously stated from the very beginning of the theme.

The notes are quite widely spread, however, on the circle of fifths. The two brown notes are extraneous to a major key. Because the needle of our tonal compass rotates clockwise, it could give notice of a modulation towards the dominant (degree V) or even more distant a key. Or it could give notice of a minor key, in which the degrees VI and VII would be varying.

As a matter of fact, the first two bars of the score contain all characteristics (degrees I through V) of a major key, so our auditory memory records that key until a possible modulation leads us to another key. On the score, we represent these initial notes using the key of A flat major, on a staff whose key signature therefore includes four flats. (If need be, we could consider the key of G sharp major, especially if the notes were modulating from a key signature made of sharps.)

The first note extraneous to the key of A flat major is the E natural at bar 3. We could analyze it as a modulation towards F minor, the relative minor key, but it is customary rather to analyze it as a passing note, for these four reasons:

The second note extraneous to the key of A flat major is the A natural at bar 5. We could also analyze it as a modulation towards B flat minor, the subsequent relative minor key on the circle of fifths, but it is also customary rather to analyze it as a passing note, for two of the four previous reasons:

Of course, for that A natural, the two reasons for excluding a modulation are less strong than the four reasons for the previous E natural. That first example, however, deserves further discussion. The various arguments, often put forth in most treatises on music theory, are not all equally acceptable.

Actually, the A natural (respectively, E natural) which would suggest a modulation is denied by the A flat (respectively, E flat) that follows but, above all, it itself follows the A flat (respectively, E flat) heard initially. Because the beginning of the theme unambiguously states the key, in order to introduce a true modulation, the composer would have to insist on those extraneous notes.

Here too, the first musical impression is the right one. Those false modulations confirm how our auditory memory is powerful.

For the first time, that theme shows how successive note pitches can be meaningful (whereas, previously, we were not interested in octave jumps or interval inversions).

The E natural encountered at bar 3 is considered a passing note between two notes of the key, because it is part of an ascending chromatic scale. (The same reasoning would apply to a descending chromatic scale.)

The argument consisting of considering or discarding a note, according to the down- or upbeat it is located on, is an argument to be used with care. As a matter of fact, down- or upbeats only exist after barlines have been placed on a score. In the currrent context of a musical dictation, our sound example exists, but the corresponding score does not exist yet. We talk of bars only to delimit a musical phrase or fragment. At present, the only possibility we have for segmenting a theme is using the repeat of the theme (or of a fragment of the theme) to determine the length of the theme or fragment.

Segmentating a musical phrase into measures of equal length is a complex problem beyond the scope of the present study. Even if note acccentuation is of some importance, it is hence difficult to refer to it to determine a key.

Numerous counterexamples, however, will show that using note accentuation or duration is hazardous in rating the tonal importance of the notes.

Here is the theme of the adagietto (4th movement) from G. Mahler's symphony n° 5:

Beyond the theme, played by violins, cellos repeat the theme with slightly modifying it.

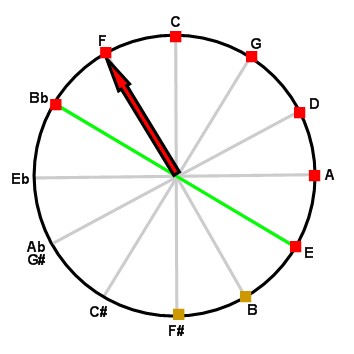

Here is the representation of the notes of the theme on the circle of fifths:

In G. Mahler's theme, beyond a short introduction (not shown here), we more or less find the same characteristics as in L. v. Beethoven's theme above. The first three bars of the score contain the notes characteristic of the key of F major. Moreover, the first five notes characterize a perfect cadence.

Further on, as in the previous theme, our tonal compass rotates towards the key of the dominant, or even further (or else towards some relative minor key).

The first note extraneous to the key of F major is the B natural at bar 6. It is a passing note that makes part of a descending chromatic scale, because the B natural is immediately denied by the subsequent B flat. That bar, indeed, shows a counterexample of a long note being located on an upbeat.

The second note extraneous to the key is the F sharp at bars 7 and 8. It is also a (replicated) passing note. The F sharp is quickly denied by the subsequent F natural. That example shows that a passing note can, on the contrary, have a short duration while being located on a downbeat.

At last, that theme shows the weaknesses of arguments only based on note duration and accentuation. On the contrary, it confirms how our auditory memory is powerful. As long as notes extraneous to the key heard first are not confirmed, our tonal compass swings back and forth but does not significantly deviate from its original orientation.

|

Jean-Pierre Vial January 2021 |

|

|

|

|